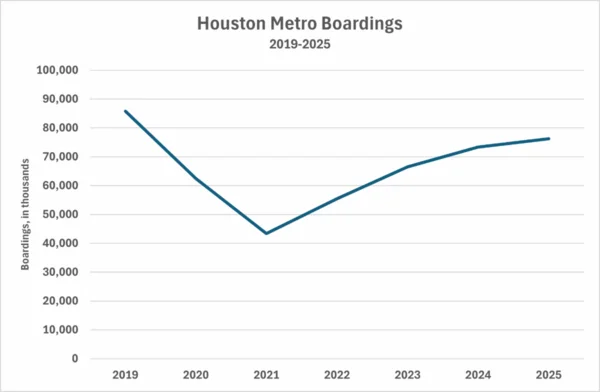

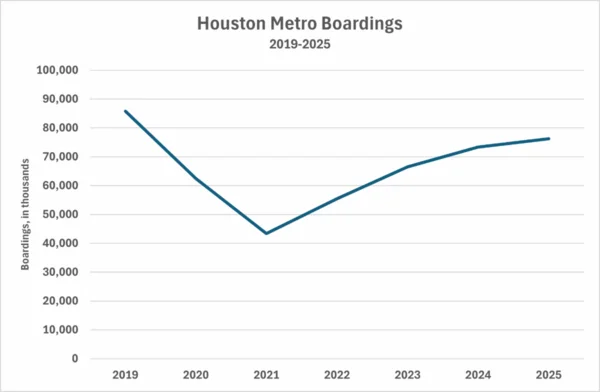

Houston Metro recently released its year-end ridership report.1 It shows that total ridership marginally improved last year from 73.3 to 76.3 million boardings, a 4% increase.2 Immediately before the pandemic, Metro had nearly 86 million boardings, so it is still about 11% shy of returning to pre-pandemic ridership levels, but has seen a nearly 15% increase since the change in leadership at Metro ushered in by the Whitmire administration.

Photo credit: Bill King Blog

Photo credit: Bill King Blog

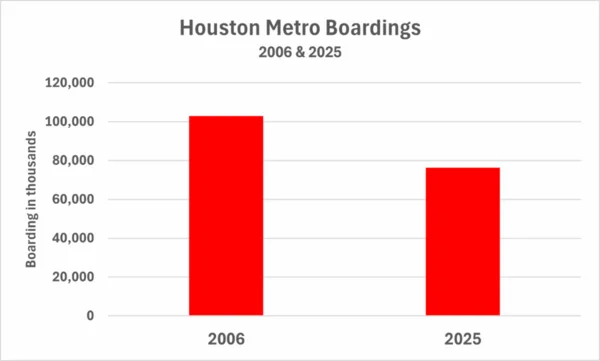

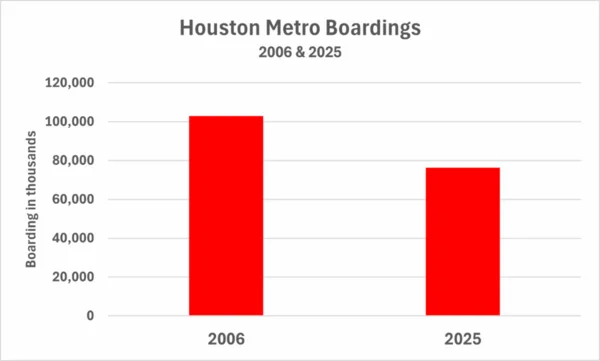

Just for some longer-term historical perspective, keep in mind that Metro hit its all-time high in ridership almost 20 years ago, in 2006, at 103 million boardings. After that, ridership gradually declined before falling off a cliff when the pandemic hit. So, after investing over $20 billion in transit over the last two decades, we have managed to reduce ridership by 26%.

Photo credit: Bill King Blog

Photo credit: Bill King Blog

The local bus service continues to be the workhorse of the system, accounting for 77% of boardings (58.5 million). That was a 5% improvement from last year, and bus ridership is now just 1% below its pre-pandemic level.

The light rail system continued to prove what a disastrous investment it has been. Its ridership fell by 3% and is almost a third below its pre-pandemic level. The Purple and Green lines' ridership is particularly dreadful, with boardings at a fraction of the pre-construction projections. Both, along with the extension of the Red line to the north, have been cited in FTA reports as being among the worst performers in the nation, relative to their ridership projections. This is one of the reasons Houston is unlikely to ever receive any more FTA funding for LRT or BRT projects.

I would bring up the continued abysmal performance of the Uptown BRT, but it has turned into such a joke that it is hardly worth mentioning. So, let’s just leave it at this: the Uptown BRT was unquestionably the biggest waste of $200 million in Houston’s history.

The Park-and-Ride system, which mainly serves commuters from the outer suburbs, continues to lag well behind its pre-pandemic levels. There were only about 4 million boardings last year, compared to double that number before the pandemic. Still, that was up almost 10% from the previous year. I suspect this is a principally a function of the work-from-home phenomenon and that there is little Metro can do to affect the ridership. Fortunately, these commuters are willing to pay relatively high fares, and the service is easily scalable, so there is little cost to Metro for this downturn in ridership.

Metro, along with other transit agencies across the country, has been struggling with stagnant population growth in urban cores. The entire theory underlying the concept of congregate transit is that urban cores will grow and population densities will increase. However, the growth for the last two decades has been concentrated in the suburbs and the exurbs, areas with relatively low population densities. Congregate transit simply does not work in that kind of development pattern.

Public transportation plays an important role in providing transportation for those who cannot afford an automobile or are physically unable to operate one. We should support public transportation for those reasons. But the idea that transit can be used to somehow transform urban development patterns or will ever be a viable alternative to the automobile is delusional.

Note 1 – Metro’s fiscal year ends on September 30.

Note 2 – The standard method used by transit agencies to measure ridership is boardings, that is, when a person gets onto one of their vehicles. This should not be confused with the total number of people who use the system daily or the total number of trips the boarding replaces. Most transit riders are making a round trip, so the total number of riders will typically be about half the boardings. Also, many trips in the system require the rider to change buses or change from a bus to a train, or vice versa. Therefore, just counting boardings overestimates the total trips replaced.

Photo credit: Bill King Blog

Photo credit: Bill King Blog Photo credit: Bill King Blog

Photo credit: Bill King Blog